The Wilderness Within

I was 14 the first time I set foot on Isle of the Pines, the remote 10- acre paradise that Dorothy Molter (aka The Root Beer Lady) called home for more than 50 years. By the time I arrived, she had been there for nearly 30 years, but it felt as if I was the first person who had ever been there- never mind that by that time she was receiving more than 6,000 visitors every summer. In the one-woman play, Root Beer Lady, (directed by Mishawaka alumnus Addie Gorlin Han) that just wrapped up its run at the History Theatre in St. Paul, Dorothy describes the awe she felt as she first stepped on the island as a young woman in 1931. She was chastised by her father and host for failing to help unload the canoes as she stood amongst the pines and birch trees and soaked in the sights, smells and feelings of this unspoiled wilderness.

It still takes traversing 6 portages and 8 lakes to set foot on the now vacant Isle of the Pines, but in 1931 it really must have felt like the edge of the world. Whatever Dorothy found on that first visit stuck, and she went on to spend winters and summers in what is now the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness- often alone, but seldom lonely, as her avatar reminded the audience. She was probably too busy to be lonely. She had wood to split, vital chores to do -not to mention the root beer she made from birch sap and offered to thirsty canoeists who dropped in. (It tasted wonderful!) She defied all the expectations of the age- a woman alone in the wilderness- and found a fair measure of success and a greater satisfaction than most of us can imagine. She was a frontier-women in every sense of the word.

By the time the summer camping movement began at the turn of the 20th century, most of the physical frontiers of America had been explored. In many respects this is what gave rise to the creation of summer camps. The early pioneers of camping created a “manufactured wilderness” for children to discover, just as social commentators began to feel that modern technologies (electricity, indoor plumbing, and automobiles!) were softening the youth of America. With the final frontier, in James T. Kirk’s famous description of space, left to the province of billionaires and select astronauts, and the meta-verse as vague and fulfilling as a B grade sci-fi matinee, we are left to look elsewhere.

Don’t get me wrong, I know there are frontiers still to explore- whether in the real or digital world. It’s hard to deny that Artificial Intelligence will play an ever-increasing role in our daily lives-as the program that suggests my next words reminds me. But I am also reminded that it’s “artificial.”

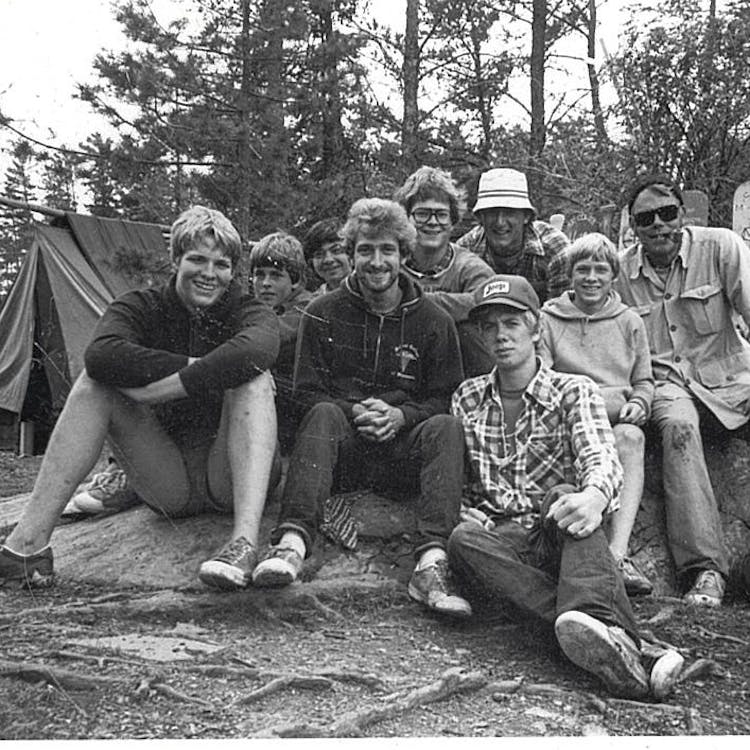

One need not be the first to step on the shore of a remote island to experience the sense of awe that comes with new discovery and an authentic experience. Sometimes, surprisingly, we don’t even need to venture too far to find a frontier. The 300 children that spend part of their summer at Camp Mishawaka won’t be the first to do so, but frontiers and discoveries await them, just as they await those of us whose job it is to guide them. Dorothy defined wilderness for the audience as a place where man (and woman!) can only visit, not reside. ( She defied that for more than 50 years.) However long each of us gets to visit this wilderness, or Camp Mishawaka, it’s clear that we leave just a bit better, connected to those around us and the natural world.

Perhaps Dorothy’s fellow denizen of the Boundary Waters Area, Sigurd Olsen, said it best when he wrote, What a man (or woman) finally becomes, how they adjust themselves to their world, is a composite of all the horizons they have endured. For they have marked them and left indelible imprints on their attitude and convictions and given their life direction.

Someday I hope to return to the Isle of the Pines, even if there is no luke-warm root beer waiting for me. But I am almost sure to find something new.